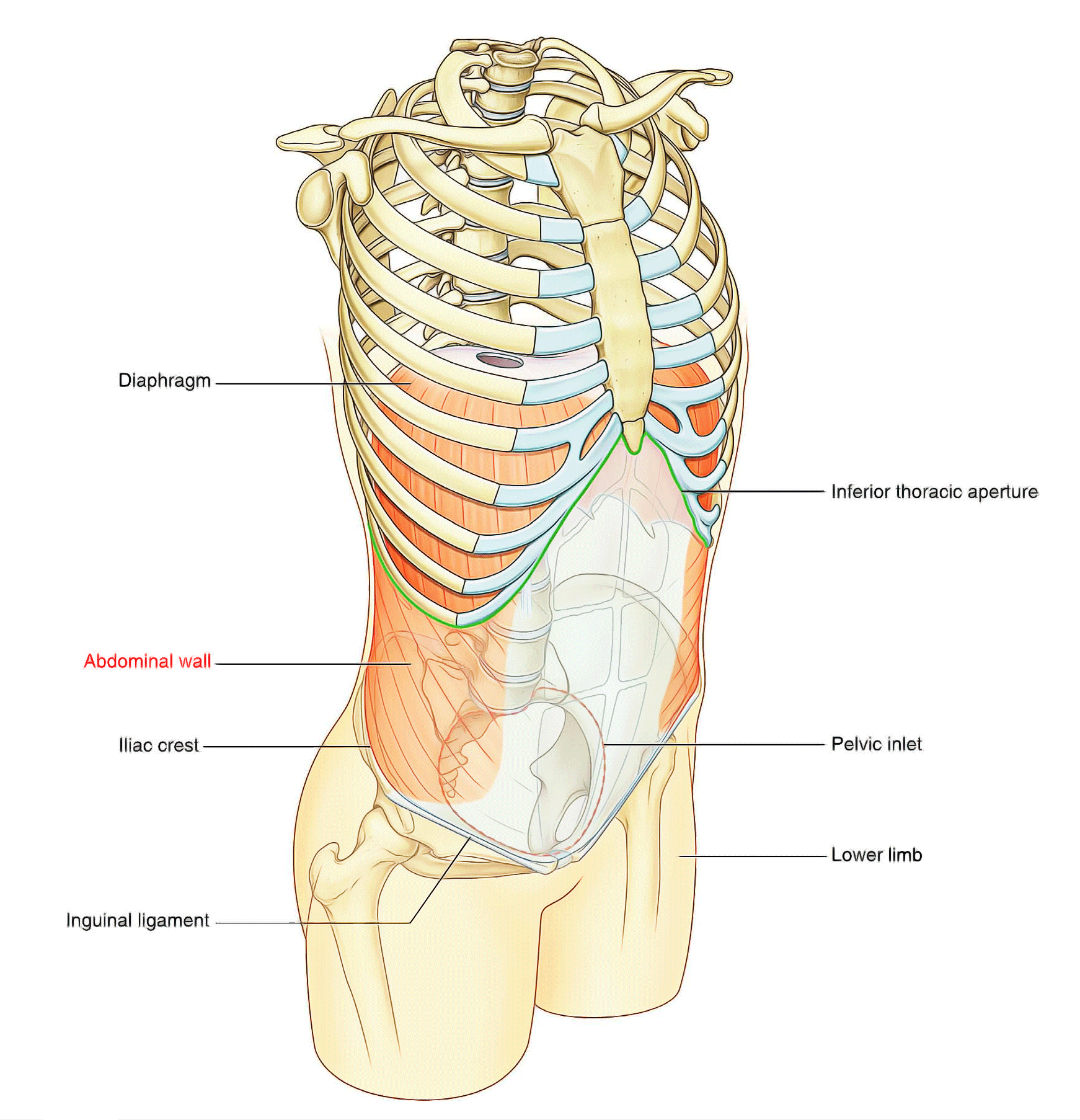

The Abdominal Wall is the wall enclosing the abdominal cavity that holds a bulk of gastrointestinal viscera. A good amount of area is covered by the abdominal wall. The xiphoid process and costal margins bound it superiorly, the vertebral column posteriorly and the upper parts of the pelvic bones inferiorly. Skin, superficial fascia (subcutaneous tissue), muscles and their associated deep fascias, extraperitoneal fascia, and parietal peritoneum together compose its layers. Among the most common surgical procedures, Incision and closure of the abdominal wall is the most frequent one.

Superficial fascia

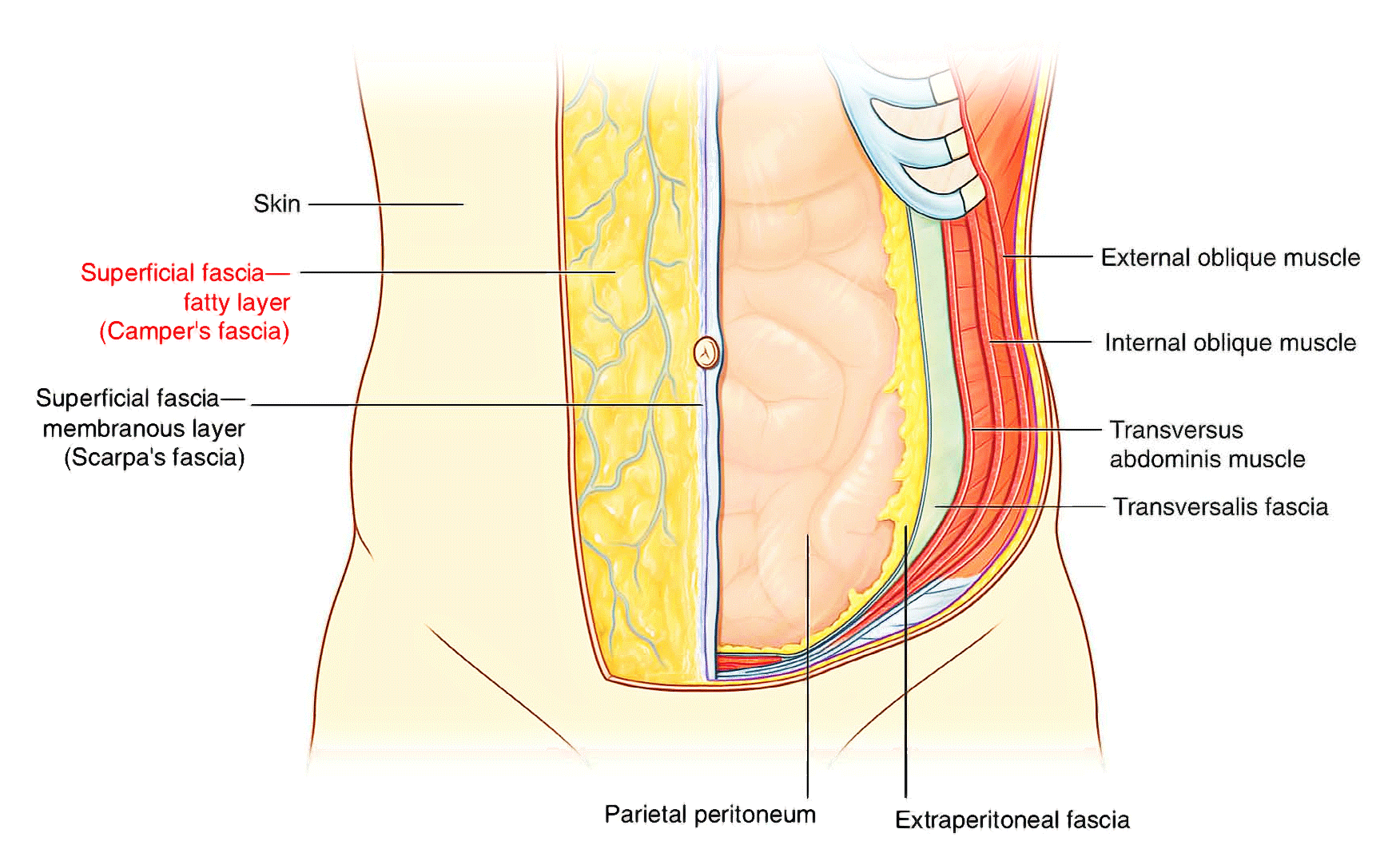

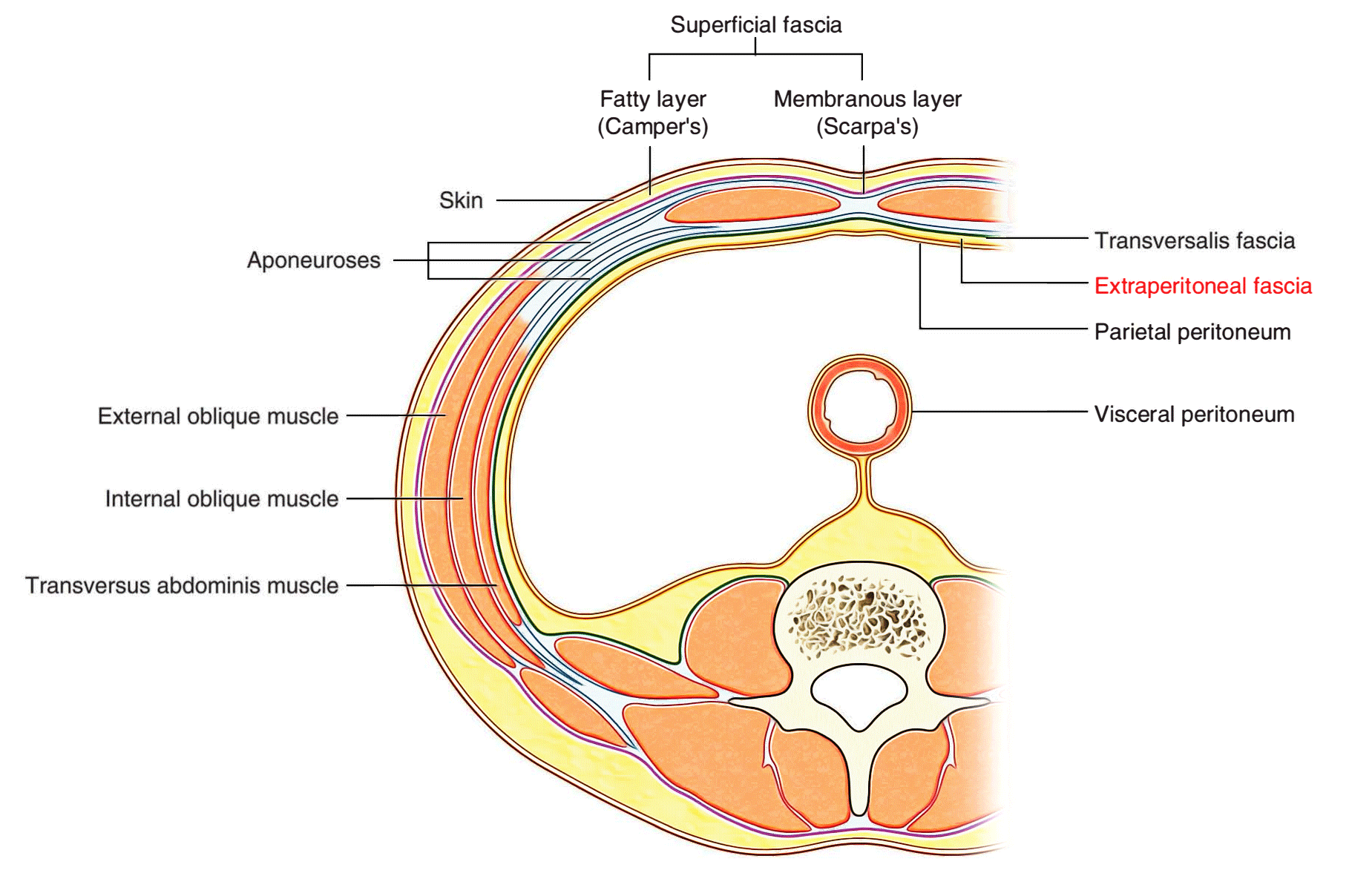

The superficial fascia of the abdominal wall (subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen) is a layer of fatty connective tissue. However, in the lower region of the anterior part of the abdominal wall, below the umbilicus, it forms two layers: a superficial fatty layer and a deeper membranous layer.

Superficial layer

The superficial fatty layer of superficial fascia (Camper’s fascia) contains fat and varies in thickness. It is continuous over the inguinal ligament with the superficial fascia of the thigh and with a similar layer in the perineum.

In men, this superficial layer continues over the penis and, after losing its fat and fusing with the deeper layer of superficial fascia, continues into the scrotum where it forms a specialized fascial layer containing smooth muscle fibers (the dartos fascia). In women, this superficial layer retains some fat and is a component of the labia majora.

Deeper layer

The deeper membranous layer of superficial fascia (Scarpa’s fascia) is thin and membranous, and contains little or no fat. Inferiorly, it continues into the thigh, but just below the inguinal ligament, it fuses with the deep fascia of the thigh (the fascia lata). In the midline, it is firmly attached to the linea alba and the symphysis pubis. It continues into the anterior part of the perineum where it is firmly attached to the ischiopubic rami and to the posterior margin of the perineal membrane. Here, it is referred to as the superficial perineal fascia (Colles’ fascia).

In men, the deeper membranous layer of superficial fascia blends with the superficial layer as they both pass over the penis, forming the superficial fascia of the penis, before they continue into the scrotum where they form the dartos fascia. Also in men, extensions of the deeper membranous layer of superficial fascia attached to the pubic symphysis pass inferiorly onto the dorsum and sides of the penis to form the fundiform ligament of penis. In women, the membranous layer of the superficial fascia continues into the labia majora and the anterior part of the perineum.

Anterolateral muscles

There are five muscles in the anterolateral group of abdominal wall muscles:

- Three flat muscles whose fibers begin posterolaterally, pass anteriorly, and are replaced by an aponeurosis as the muscle continues toward the midline—the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles;

- Two vertical muscles, near the midline, which are enclosed within a tendinous sheath formed by the aponeuroses of the flat muscles—the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles.

Each of these five muscles has specific actions, but together the muscles are critical for the maintenance of many normal physiological functions. By their positioning, they form a firm, but flexible, wall that keeps the abdominal viscera within the abdominal cavity, protects the viscera from injury, and helps maintain the position of the viscera in the erect posture against the action of gravity.

In addition, contraction of these muscles assists in both quiet and forced expiration by pushing the viscera upward (which helps push the relaxed diaphragm further into the thoracic cavity) and in coughing and vomiting.

All these muscles are also involved in any action that increases intraabdominal pressure, including parturition (childbirth), micturition (urination), and defecation (expulsion of feces from the rectum).

Abdominal wall muscles summary

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| External oblique | Muscular slips from the outer surfaces of the lower eight ribs (ribs V to XII) | Lateral lip of iliac crest; aponeurosis ending in midline raphe (linea alba) | Anterior rami of lower six thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T12) | Compress abdominal contents; both muscles flex trunk; each muscle bends trunk to same side, turning anterior part of abdomen to opposite side |

| Internal oblique | Thoracolumbar fascia; iliac crest between origins of external and transversus; lateral two-thirds of inguinal ligament | Inferior border of the lower three or four ribs; aponeurosis ending in linea alba; pubic crest and pectineal line | Anterior rami of lower six thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T1 2) and L1 | Compress abdominal contents; both muscles flex trunk; each muscle bends trunk and turns anterior part of abdomen to same side |

| Transversus abdominis | Thoracolumbar fascia; medial lip of iliac crest; lateral one-third of inguinal ligament; costal cartilages lower six ribs (ribs VII to XII) | Aponeurosis ending in linea alba; pubic crest and pectineal line | Anterior rami of l ower six thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T1 2) and L1 | Compress abdominal contents |

| Rectus abdominis | Pubic crest, pubic tubercle, and pubic symphysis | Costal cartilages of ribs V to VII; xiphoid process | Anterior rami of lower seven thoracic spinal nerves (T7 to T1 2) | Compress abdominal contents; flex vertebral column; tense abdominal wall |

| Pyramidalis | Front of pubis and pubic symphysis | Into linea alba | Anterior ramus of T1 2 | Tenses the linea alba |

Flat muscles

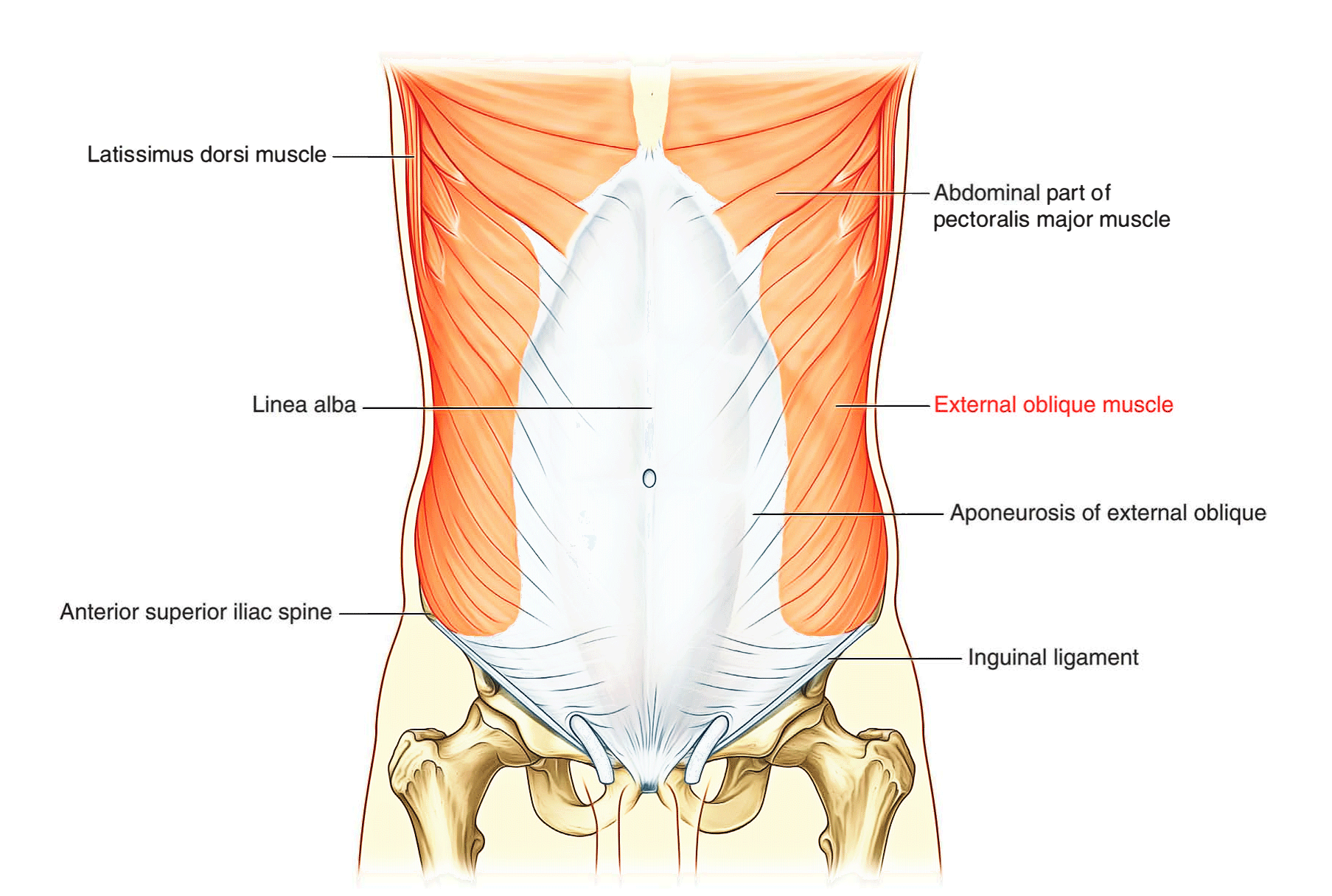

External oblique

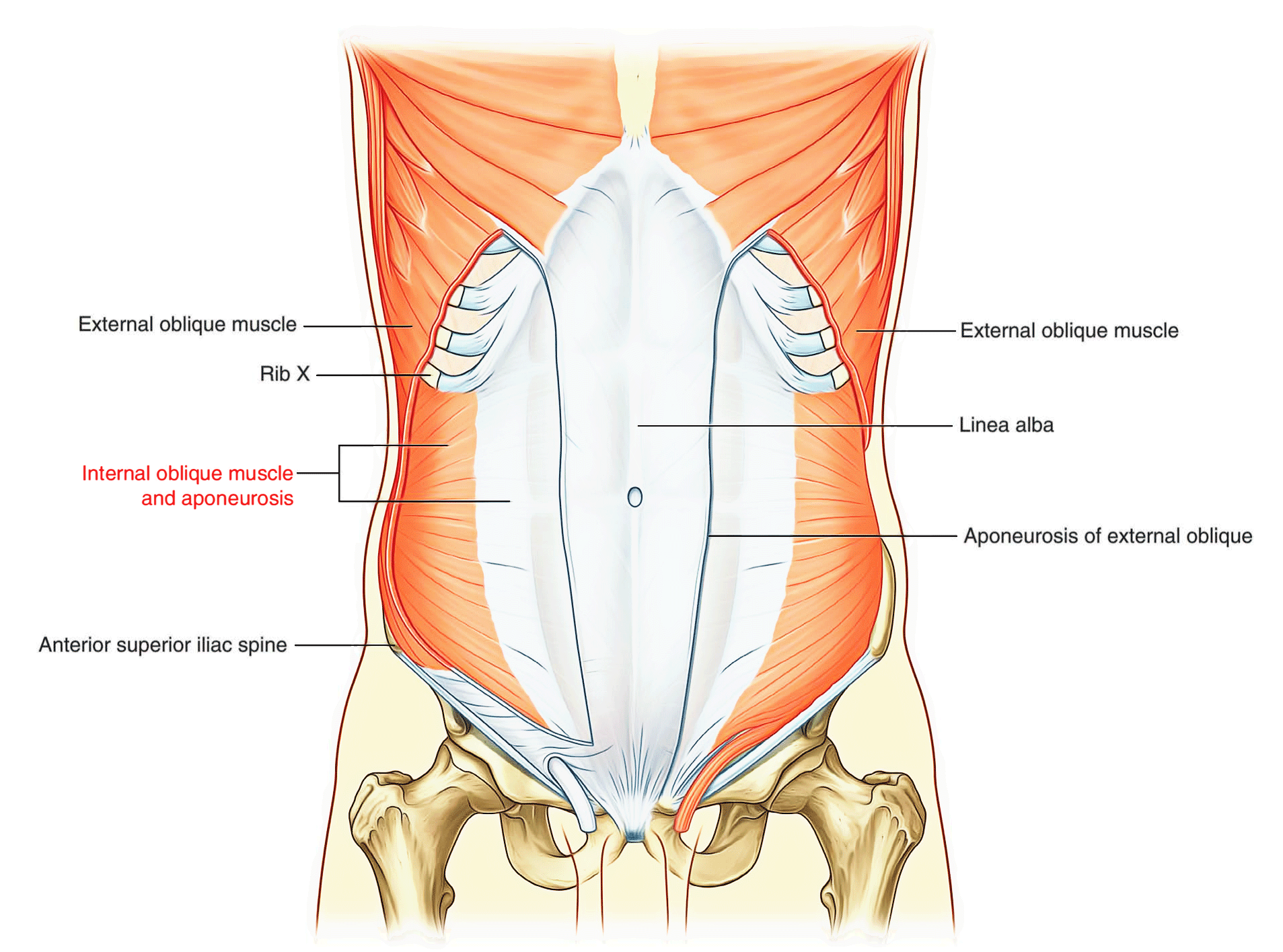

The most superficial of the three flat muscles in the anterolateral group of abdominal wall muscles is the external oblique, which is immediately deep to the superficial fascia. Its laterally placed muscle fibers pass in an inferomedial direction, while it’s large aponeurotic component covers the anterior part of the abdominal wall to the midline. Approaching the midline, the aponeuroses are entwined, forming the linea alba, which extends from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis.

Associated ligaments

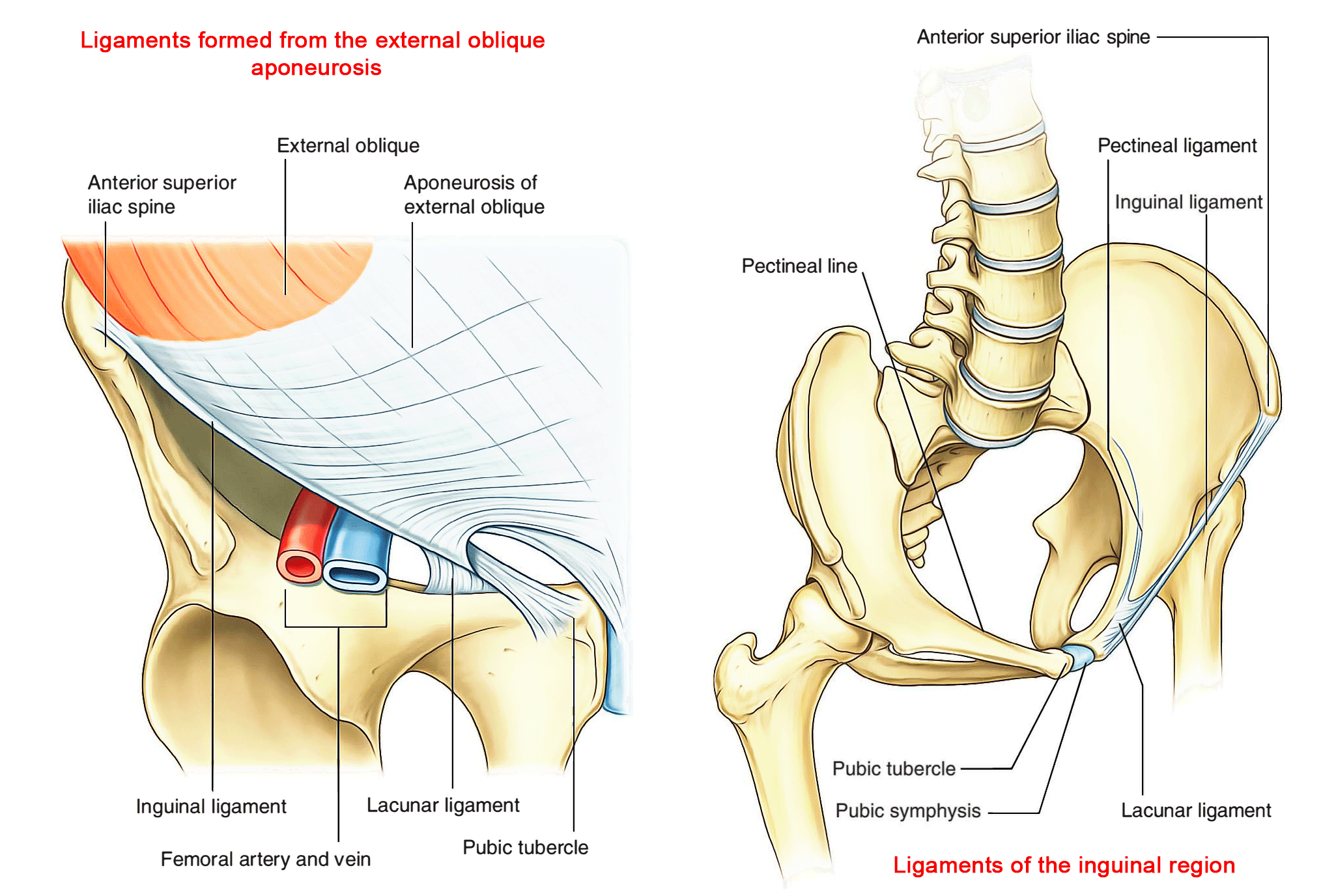

The lower border of the external oblique aponeurosis forms the inguinal ligament on each side. This thickened reinforced free edge of the external oblique aponeurosis passes between the anterior superior iliac spine laterally and the pubic tubercle medially (Right side in above image). It folds under itself forming a trough, which plays an important role in the formation of the inguinal canal.

Several other ligaments are also formed from extensions of the fibers at the medial end of the inguinal ligament:

- The lacunar ligament is a crescent-shaped extension of fibers at the medial end of the inguinal ligament that pass backward to attach to the pecten pubis on the superior ramus of the pubic bone.

- Additional fibers extend from the lacunar ligament along the pecten pubis of the pelvic brim to form the pectineal (Cooper’s) ligament.

Internal oblique

Deep to the external oblique muscle is the internal oblique muscle, which is the second of the three flat muscles. This muscle is smaller and thinner than the external oblique, with most of its muscle fibers passing in a superomedial direction. Its lateral muscular components end anteriorly as an aponeurosis that blends into the linea alba at the midline.

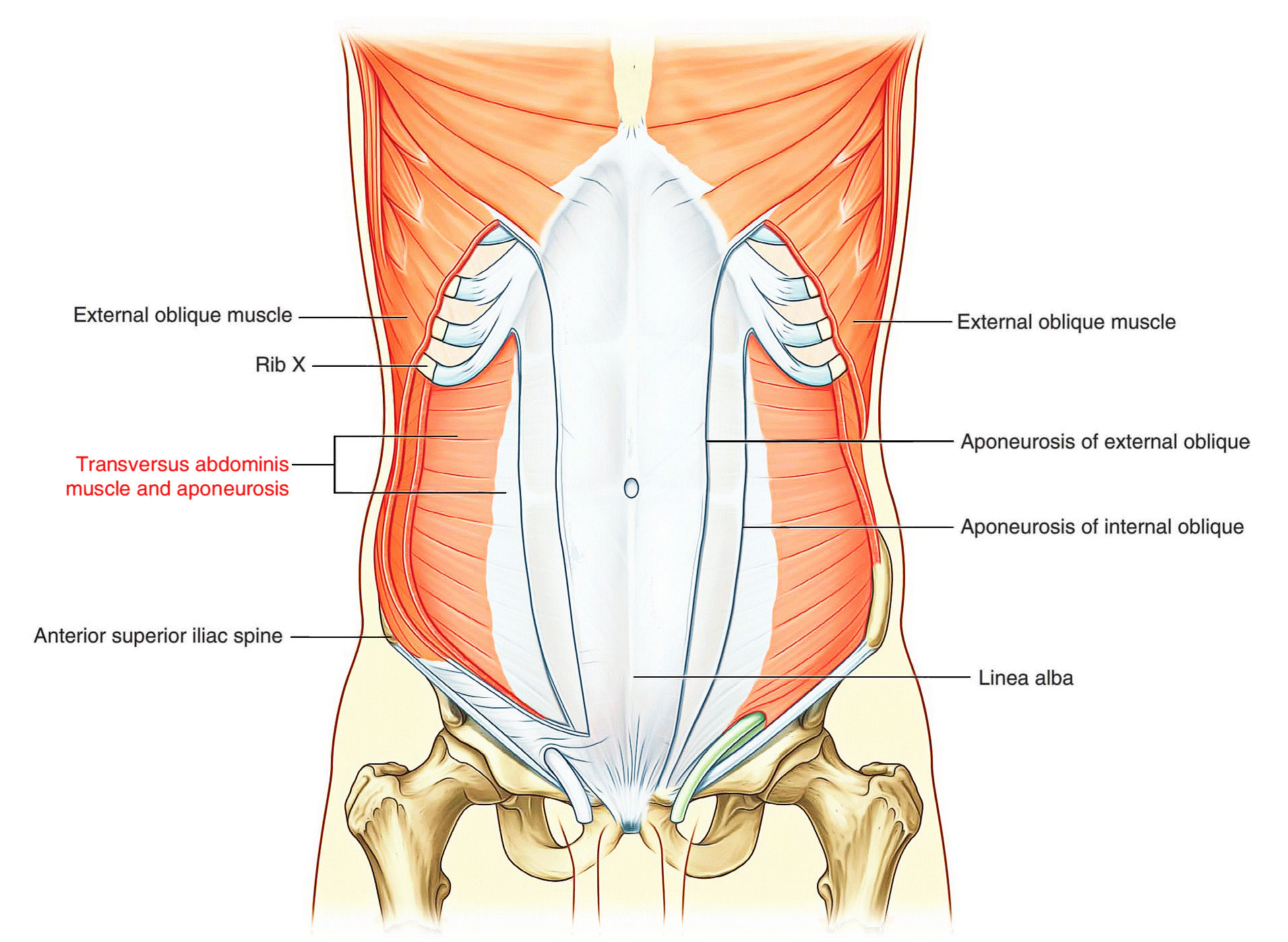

Transversus abdominis

Deep to the internal oblique muscle is the transversus abdominis muscle, so named because of the direction of most of its muscle fibers. It ends in an anterior aponeurosis, which blends with the linea alba at the midline.

Transversalis fascia

Each of the three flat muscles is covered on its anterior and posterior surfaces by a layer of deep (or investing) fascia. In general, these layers are unremarkable except for the layer deep to the transversus abdominis muscle (the transversalis fascia), which is better developed.

The transversalis fascia is a continuous layer of deep fascia that lines the abdominal cavity and continues into the pelvic cavity. It crosses the midline anteriorly, associating with the transversalis fascia of the opposite side, and is continuous with the fascia on the inferior surface of the diaphragm. It is continuous posteriorly with the deep fascia covering the muscles of the posterior abdominal wall and attaches to the thoracolumbar fascia.

After attaching to the crest of the ilium, the transversalis fascia blends with the fascia covering the muscles associated with the upper regions of the pelvic bones and with similar fascia covering the muscles of the pelvic cavity. At this point, it is referred to as the parietal pelvic (or endo- pelvic) fascia.

There is therefore a continuous layer of deep fascia surrounding the abdominal cavity that is thick in some areas, thin in others, attached or free, and participates in the formation of specialized structures.

Vertical muscles

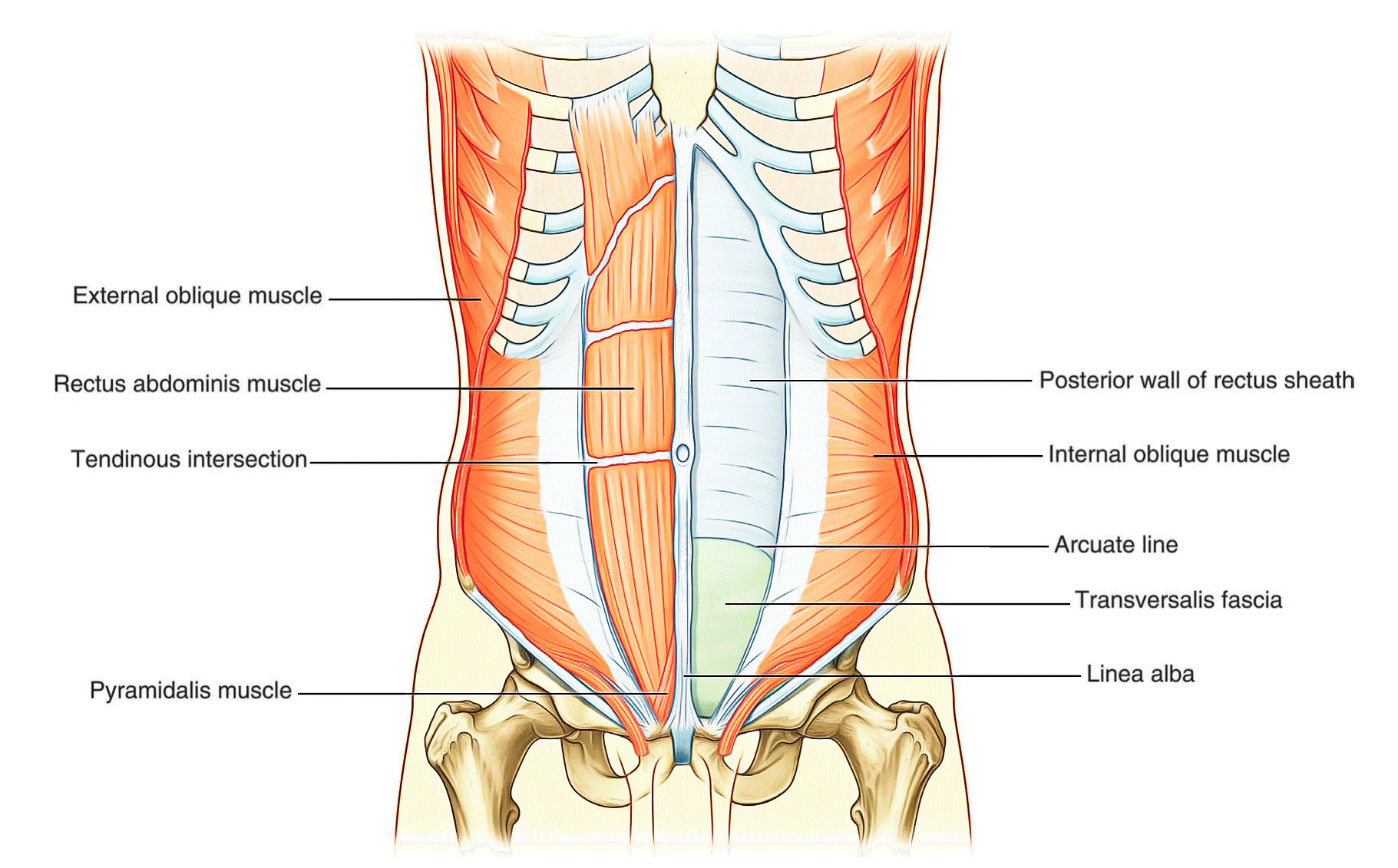

The two vertical muscles in the anterolateral group of abdominal wall muscles are the large rectus abdominis and the small pyramidalis.

Rectus abdominis

The rectus abdominis is a long, flat muscle and extends the length of the anterior abdominal wall. It is a paired muscle, separated in the midline by the linea alba, and it widens and thins as it ascends from the pubic symphysis to the costal margin. Along its course, it is intersected by three or four transverse fibrous bands or tendinous intersections. These are easily visible on individuals with a well-developed rectus abdominis.

Pyramidalis

The second vertical muscle is the pyramidalis. This small, triangular muscle, which may be absent, is anterior to the rectus abdominis and has its base on the pubis, and its apex is attached superiorly and medially to the linea alba.

Rectus sheath

The rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles are enclosed in an aponeurotic tendinous sheath (the rectus sheath) formed by a unique layering of the aponeuroses of the external and internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles.

The rectus sheath completely encloses the upper three- quarters of the rectus abdominis and covers the anterior surface of the lower one-quarter of the muscle. As no sheath covers the posterior surface of the lower quarter of the rectus abdominis muscle, the muscle at this point is in direct contact with the transversalis fascia.

The formation of the rectus sheath surrounding the upper three-quarters of the rectus abdominis muscle has the following pattern:

- The anterior wall consists of the aponeurosis of the external oblique and half of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique, which splits at the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis.

- The posterior wall of the rectus sheath consists of the other half of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis.

At a point midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis, corresponding to the beginning of the lower one-quarter of the rectus abdominis muscle, all of the aponeuroses move anterior to the rectus muscle. There is no posterior wall of the rectus sheath and the anterior wall of the sheath consists of the aponeuroses of the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transversus abdominis muscles. From this point inferiorly, the rectus abdominis muscle is in direct contact with the transversalis fascia. Marking this point of transition is an arch of fibers (the arcuate line).

Extraperitoneal Fascia

[Transverse section showing the layers of the abdominal wall]

Deep to the transversalis fascia is a layer of connective tissue, the extraperitoneal fascia, which separates the transversalis fascia from the peritoneum. Containing varying amounts of fat, this layer not only lines the abdominal cavity but is also continuous with a similar layer lining the pelvic cavity. It is abundant on the posterior abdominal wall, especially around the kidneys, continues over organs covered by peritoneal reflections, and, as the vasculature is located in this layer, extends into mesenteries with the blood vessels. Viscera in the extraperitoneal fascia are referred to as retroperitoneal.

In the description of specific surgical procedures, the terminology used to describe the extraperitoneal fascia is further modified. The fascia toward the anterior side of the body is described as preperitoneal (or, less commonly, properitoneal) and the fascia toward the posterior side of the body has been described as retroperitoneal.

Examples of the use of these terms would be the continuity of fat in the inguinal canal with the preperitoneal fat and a transabdominal preperitoneal laparoscopic repair of an inguinal hernia.

Peritoneum

Deep to the extraperitoneal fascia is the peritoneum. This thin serous membrane lines the walls of the abdominal cavity and at various points, reflects onto the abdominal viscera, providing either a complete or a partial covering. The peritoneum lining the walls is the parietal peritoneum; the peritoneum covering the viscera is the visceral peritoneum. The peritoneum bolsters and protects the abdominal organs and acts as the major channel for the connected lymph vessels, nerves and abdominal arteries and veins.

The continuous lining of the abdominal walls by the parietal peritoneum forms a sac. This sac is closed in men but has two openings in women where the uterine tubes provide a passage to the outside. The closed sac in men and the semiclosed sac in women is called the peritoneal cavity.

Innervation

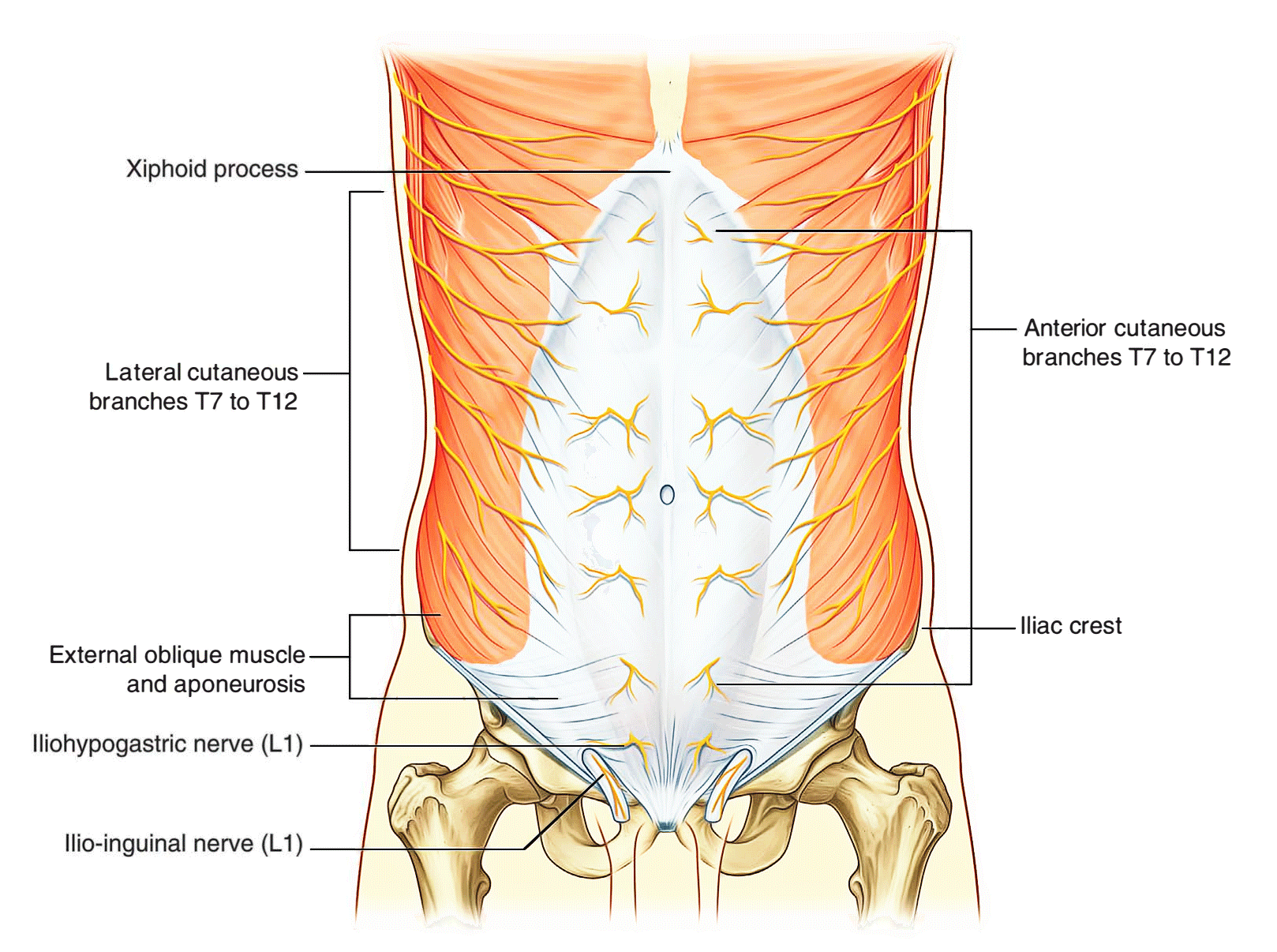

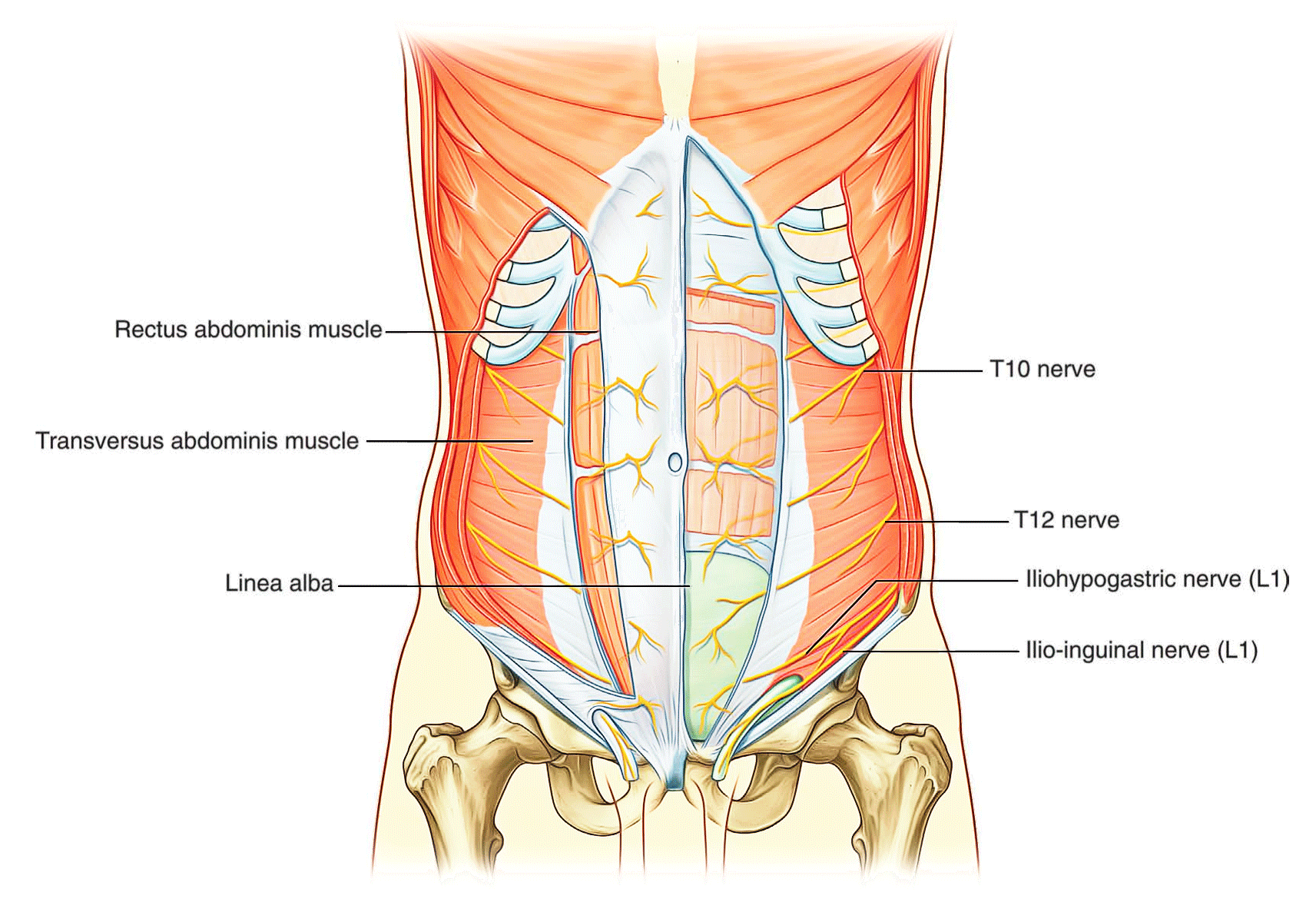

The skin, muscles, and parietal peritoneum of the anterolateral abdominal wall are supplied by T7 to Tl2 and L1 spinal nerves. The anterior rami of these spinal nerves pass around the body, from posterior to anterior, in an infero-medial direction. As they proceed, they give off a lateral cutaneous branch and end as an anterior cutaneous branch.

The intercostal nerves (T7 to T11) leave their intercostal spaces, passing deep to the costal cartilages, and continue onto the anterolateral abdominal wall between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. Reaching the lateral edge of the rectus sheath, they enter the rectus sheath and pass posterior to the lateral aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle. Approaching the midline, an anterior cutaneous branch passes through the rectus abdominis muscle and the anterior wall of the rectus sheath to supply the skin.

Spinal nerve T12 (the subcostal nerve) follows a similar course as the intercostals. Branches of L1 (the iliohypogastric nerve and ilio-inguinal nerve), which originate from the lumbar plexus, follow similar courses initially, but deviate from this pattern near their final destination.

Along their course, nerves T7 to T12 and L1 supply branches to the anterolateral abdominal wall muscles and the underlying parietal peritoneum. All terminate by supplying skin:

- Nerves T7 to T9 supply the skin from the xiphoid process to just above the umbilicus.

- T10 supplies the skin around the umbilicus.

- Tll, T12, and L1 supply the skin from just below the umbilicus to, and including, the pubic region.

- Additionally, the ilio-inguinal nerve (a branch of L1) supplies the anterior surface of the scrotum or labia majora, and sends a small cutaneous branch to the thigh.

Arterial supply and venous drainage

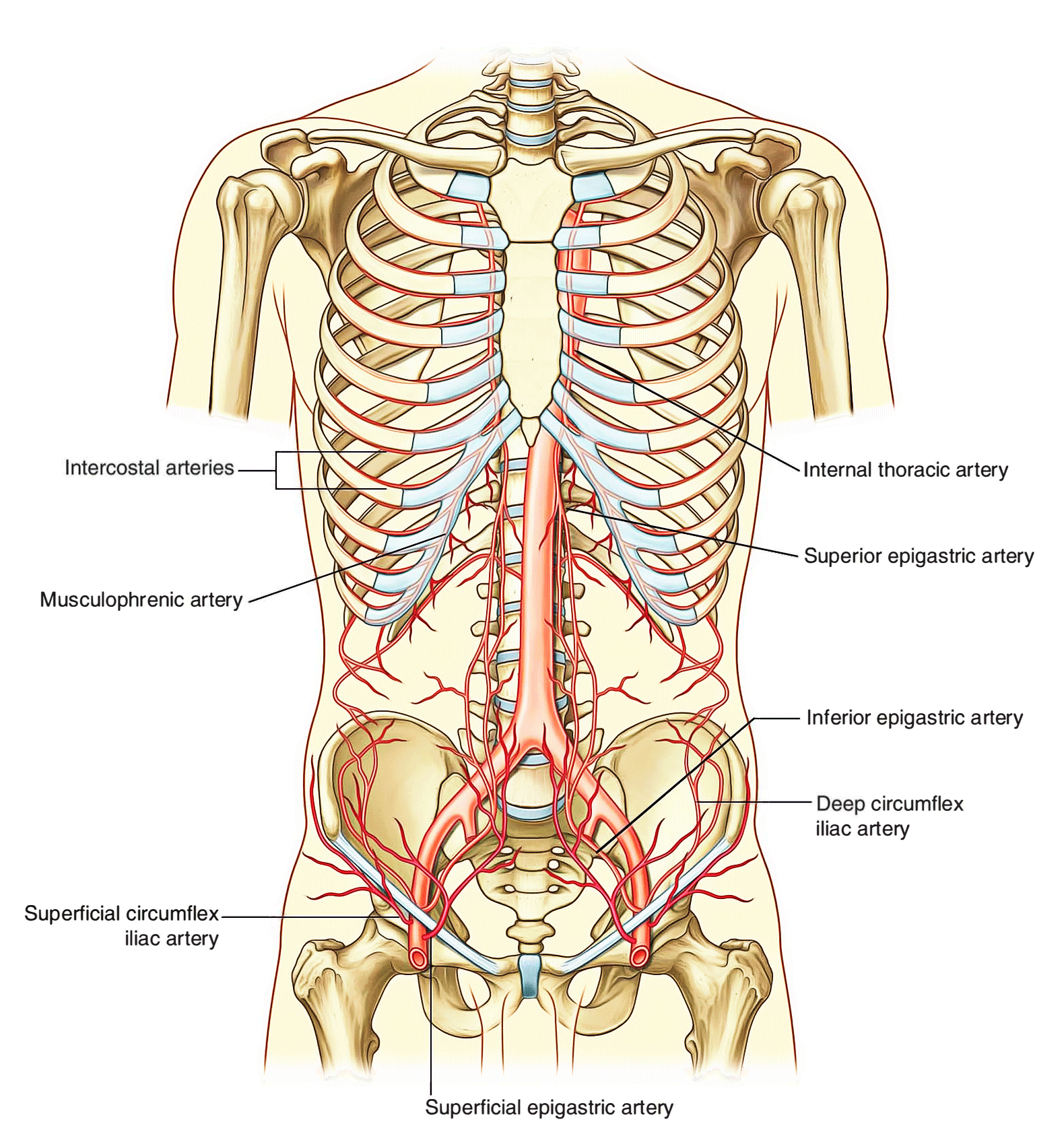

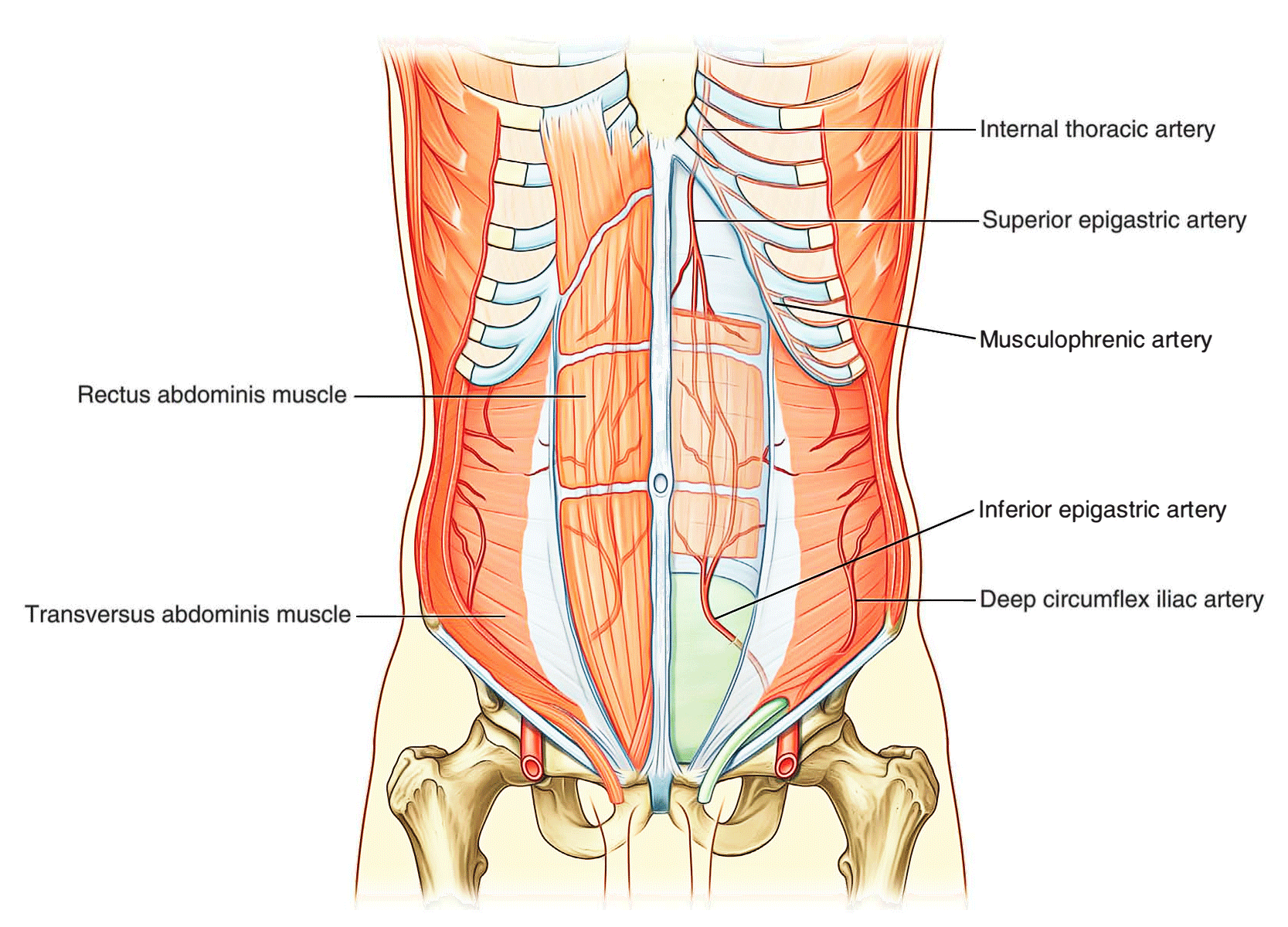

Numerous blood vessels supply the anterolateral abdominal wall.

Superficially:

- the superior part of the wall is supplied by branches from the musculophrenic artery, a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery, and

- The inferior part of the wall is supplied by the medially placed superficial epigastric artery and the laterally placed superficial circumflex iliac artery, both branches of the femoral artery.

At a deeper level:

- The superior part of the wall is supplied by the superior epigastric artery, a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery;

- The lateral part of the wall is supplied by branches of the tenth and eleventh intercostal arteries and the subcostal artery; and

- The inferior part of the wall is supplied by the medially placed inferior epigastric artery and the laterally placed deep circumflex iliac artery, both branches of the external iliac artery.

The superior and inferior epigastric arteries both enter the rectus sheath. They are posterior to the rectus abdominis muscle throughout their course, and anastomose with each other.

Veins of similar names follow the arteries and are responsible for venous drainage.

Lymphatic drainage

Lymphatic drainage of the anterolateral abdominal wall follows the basic principles of lymphatic drainage:

- Superficial lymphatics above the umbilicus pass in a superior direction to the axillary nodes, while drainage below the umbilicus passes in an inferior direction to the superficial inguinal nodes.

- Deep lymphatic drainage follows the deep arteries back to parasternal nodes along the internal thoracic artery, lumbar nodes along the abdominal aorta, and external iliac nodes along the external iliac artery.

(64 votes, average: 4.67 out of 5)

(64 votes, average: 4.67 out of 5)